Development and characterization of neural network-based multianalyte delta checks

Introduction

In laboratory medicine, mislabeled specimens (MLS) are pre-analytical errors where blood from one patient is given an ID label from a different patient. These errors are estimated to occur in between 0.03 to 17 specimens per 1000 specimens collected (1-4). It is likely that the lower estimates may be falsely low due to the difficulty in identifying these errors in clinical practice. When MLS are not detected, they can place one or both patients at risk of harm as clinical decisions are carried out based on incorrect data. MLS are estimated to cost 280,000 USD per million specimens collected, and cause 160,000 adverse medical events per year in the United States (5).

Pre-analytical solutions have been relatively successful at reducing the number of MLS. In one study, the implementation of barcode labels with bedside printers reduced the number of MLS by 92% (6). In a multi-institutional survey, MLS were noted to occur significantly less frequently in institutions with ongoing quality monitoring systems for specimen identification, and in institutions with 24/7 inpatient phlebotomy service (3). One approach to reducing MLS is to give patients identifying wristbands, but wristband errors can result in downstream MLS error. To reduce the number of wristband errors, the College of American Pathologists performed a study involving 217 institutions where phlebotomists were tasked with continuously evaluating patient wristbands for error. This strategy reduced wristband errors from 7.40% to 3.05% (7).

In cases where pre-analytical strategies fail, post-analytical methods to detect MLS have been developed. Delta checks are one such system and are widely used due to the low cost of implementation. In this method, patients’ analytical test results from two different time points are compared. If the value change exceeds a pre-determined threshold, the results are flagged and either reviewed, repeated, or the specimen is recollected (8). Multiple strategies using this framework have been implemented. Thresholds, for example, can be applied to the absolute change in value (current result minus the previous result), or a relative change in value (current result divided by the previous result). Change velocities (change in value divided by the difference in collection time) can also be used. No standard acceptable tolerances have been established, although median values have been reported (8). Despite widespread implementation of delta-checks in clinical laboratories, the value of this strategy is questionable. Receiver operator characteristics curve (ROC) analysis has shown that the best performing delta check was for mean corpuscular volume (MCV) which only achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.90 (9). In one analysis, multiple analytes were combined and a weighted cumulative delta check was implemented. Although this model achieved promising results with a maximum AUC of 0.98 (10), the same data was used to both generate and test their model, introducing a significant source of potential bias.

Recently, delta checks were revisited using machine learning techniques. An AUC of 0.97 was achieved using a support vector machines (SVM) method (11), showing that a better performance could be achieved as compared logistical regression (AUC =0.92). Despite their achievement, the researchers limited their analysis to a rigid panel of 11 analytes, and only examined specimens collected within 36 hours of one another. This restrictive approach likely meant that only a small minority of all the blood-specimens collected at their institution could be evaluated by their model. Although they compared their method to a weighted logistical regression model, these were also limited to the same 11 analytes as their SVM method, even if more tests were actually performed.

To expand and improve upon previous work, we devised two novel machine learning methods to identify MLS using neural networks. In one approach, the results from rigid analyte panels were used to identify MLS. In the second approach, neural networks were created that were not limited to a specific panel of analytes, but instead could be given any combination of analytes. For both approaches, different neural networks were created and evaluated for different ranges of time deltas. The performance of each neural network was compared directly to the current delta check strategy used at our institution.

Methods

Data processing

A MatLab code was created to automate all data processing, and to create and test all neural networks. MATLAB R2018b (MathWorks, version 9.5.0.944444, Natick, Massachusetts, USA) was used.

Datasets

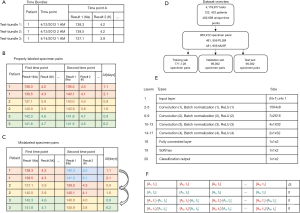

All analytical test results performed on our automated core chemistry and immunoassay analyzers at our institution between 4/12/2012 to 1/30/2014 (1.8 years) were collected. All patient medical record numbers were de-identified via assignment of unique numeric codes that were not tied to the original numbers. The complete list of analytical tests is shown in Table S1. The test results were sorted by patient and time of collection, and bundled with all other test results from the same patient that were collected at the same time (Figure 1A). A total of 4,119,977 analytical tests from 122,433 patients over 462,998 unique time points were obtained. Test-bundles with less than 5 analytes were discarded from the set.

Combinations of two test-bundles from a single patient were linked to create properly-labeled-specimen-pairs (PLSP) (Figure 1B). Every possible combination was produced, and the time between each linked pair was recorded. The delta time, Δt, is the time difference between two collection times:

Δt = tB-tA

where tA and tB are the first and second time points. PLSP with a Δt greater than 10 days were discarded from the dataset.

Mislabeled specimen simulation

Mislabeled-specimen-pairs (MLSP) were created by randomly reassigning the analytical test results from the second time point to a different patient (Figure 1C). Test-bundles were always reassigned to different patients that had the same set of analytes performed. In cases where there were insufficient unique patients to reassign the test results to a different patient, both the MLSP and corresponding PLSP were discarded. A total of 481,956 PLSP and MLSP (963,912 pairs in total) were created in this manner, spanning 18,886 patients. 80% of the specimen-pairs (771,128 pairs) were randomly assigned to a master-training set, while 10% (96,392 pairs) each were assigned to a validation set and a test set (Figure 1D). The data sets were then divided into five groups depending on their Δt: <1.5, 1.5–2.5, 2.5–3.5, 3.5–5, and 5–10 days.

Neural networks were created to predict if specimen-pairs were PLSP or MLSP using different methodologies described below.

Panel neural networks (PNN)

PNN were created to detect MLS when the same panel was ordered at two time points. All analytes that were not in the panels were discarded for this analysis. Specimen pairs that did not have the full panel were likewise discarded. The panels that were evaluated included the basic metabolic panel (BMP), the comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), the renal function panel (RFP), and the liver function panel (LFP). Analytes for each panel are listed in Table 1, while the number of specimen pairs used to train, validate, and test each PNN are shown in Table S2, along with neural network training parameters.

Table 1

| Panel name | Analytes |

|---|---|

| Basic metabolic panel (BMP) | Na, K, Cl, CO2, BUN, CRE, GLUC, Ca |

| Comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) | Na, K, Cl, CO2, BUN, CRE, GLUC, Ca, ALKP, ALT, AST, TBILI, TP, ALB |

| Hepatic function panel (HFP) | ALKP, ALT, AST, ALB, TBILI, DBILI, TP |

| Renal function panel (RFP) | Na, K, Cl, CO2, BUN, CRE, GLUC, Ca, ALB, PHOS |

ALB, albumin; ALKP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CA, calcium; CL, chloride; CO2, bicarbonate; CRE, creatinine; DBILI, direct bilirubin; GLUC, glucose; K, potassium; NA, sodium; PHOS, phosphorus; TBILI, total bilirubin; TP, total protein.

The prototypical neural network architecture is shown in Figure 1E, and the prototypical input layer is shown in Figure 1F. In brief, the input layer was an (N+1)×4 matrix, where N is the number of analytes in the test-panel. The first N columns each correspond to a different analyte. The first row was populated with the analytes from the first time-point, while the second row was populated with the analytes from the second time point. The third row was populated with the absolute change in value between the two time points (current result minus the previous result), while the fourth row was populated by the relative change in value (current result divided by the previous result). The cell in row 1 of the final column (column N+1) was populated by Δt in days, while cells in rows 2, 3, and 4 in the final column were left as 0. The PNNs were trained between 20 and 100 epochs each. Ten PNNs were created for each panel and for each group of Δt ranges in order to perform statistical analysis.

Open-ended neural networks (ONN)

ONN were created to detect MLS regardless of what tests were ordered at either time point. For these networks, the data sets were separated based on the number of analytes ordered at the second time point. The specimen pair data was thus divided into three groups: group 1 (5 to 8 analytes tested at the second time-point), group 2 (9 to 12 analytes), and group 3 (13 or more analytes). The number of analytical tests performed at the first time point did not affect what category the specimen pair was placed in. Likewise, the same analytes did not need to be ordered at both time points in the specimen pair. The number of specimen pairs used to train, validate, and test each ONN are shown in Table S2, along with neural network training parameters.

The structure for the ONNs is similar to that of the PNNs. The difference between the approaches was in the input layer, which consisted of a 131×4 matrix. The first 130 columns either corresponded to different analytes, or was left blank (assigned a value of zero). Similar to PNNs, the first row corresponded to the value at the first time point, the second row corresponded to the value at the second time point, the third row corresponded to the absolute change in value, and the fourth row corresponded to the relative change in value. When an analyte was not tested at a given time-point, that column was left as zero. When an analyte was only tested at the first time point and not at the second time point, row 1 was populated with the test result, and rows 2, 3, and 4 were left as zero. Similarly, when an analyte was only tested at the second time point and not the first, row 2 was populated with the result and rows 1, 3 and 4 were left as zero.

Similar to PNNs, for ONNs, the cell in the first row of the final column (column 131) was populated by Δt in days, while cells in rows 2, 3, and 4 of the final column were set to zero. The ONNs were trained between 20 and 100 epochs each. Ten ONNs were created for each panel and for each group of Δt ranges for statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

ROC analysis was performed for each neural network using the PLSP and MLSP categories as the gold standard, and the neural network output score as the analyte. The AUC was calculated for each neural network. The sensitivity and specificity were obtained for the optimal operating point (OOP) on the ROC curve as calculated by the MATLAB perfcurve function that relies on a previously described cost-function curve analysis (12). The specificity was also calculated for each neural network at the points where the sensitivities reached 50% and 80%. A positive predictive value (PPV) was calculated assuming a mislabeled-specimen frequency of 1 in 200 (0.5%). This was performed for the OOP, as well as at the points where the sensitivities were set to 50% and 80%. Neural networks performance metrics are reported as mean ± standard deviation.

Classic delta checks

The data sets used to test the PNNs and ONNs were also evaluated using the classic delta check limits used at our institution. Classic delta check limits were derived from reference change limit calculations and can be viewed in Table S1. In order to properly compare the two methods, the classic delta checks were applied to all analytes that were performed at both time points in the specimen pairs. For the PNNs, analytes that were not in a given panel were still included in the classic delta check analysis. The number of times each test was ordered in our cohort, and the mean and standard deviation change over the course of 1.5 days are described in Table S1. The PPVs for each PNN and ONN test set were calculated using the classic delta checks.

Results

ROC analysis

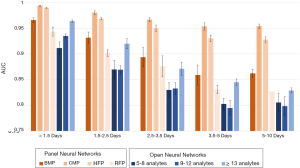

ROC analysis was applied to all neural networks. The mean AUCs for all the neural networks are compiled in Figure 2 and listed in Table S3. The best performing neural network was the CMP PNN for Δt <1.5 days, which achieved an AUC of 0.994±0.001. The CMP neural networks were the best performing of all neural networks, maintaining an AUC above 0.95 even for the 5 to 10 day Δt. The HPF PNNs were the second best performing PNNs, the BMP PNNs were third, and the RFP PNNs were fourth. In general, the ONNs performed similar to or worse than the PNNs. Performance in the ONNs improved as the number of test-analytes increased. In general, both PNNs and ONNs with low Δt performed best, and performance decreased as the Δt increased.

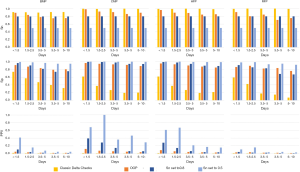

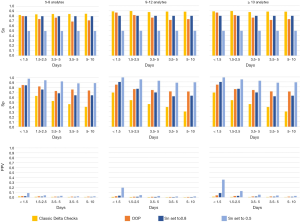

Sensitivity and specificity analysis

The sensitivities, specificities, and PPVs are shown for the PNNs and the ONNs in Tables S4 and S5, respectively. PNN results are shown in Figure 3, while the ONN results are shown in Figure 4. Similar to the AUC values, sensitivity and specificity generally decreased as the Δt increased. The CMP PNN with a Δt of <1.5 days had the highest OOP sensitivity and specificity which were 98.4% and 96.4% respectively. When sensitivities were set to 50%, the specificities for the CMP PNNs were all in excess of 99.4% regardless of the Δt. These additionally had PPVs greater than 29% for all time periods when a 0.5% MLSP frequency was assumed. The PPVs for the CMP PNNs with Δt <1.5 days and 1.5 to 2.5 days were both greater than 68%, however, these groups each represent less than 1% of the total specimen pairs. Although the BMP PNN with Δt <1.5 days had a smaller PPV (41.7%), this neural network covers a much larger proportion of all the specimen pairs (19.3%).

For the ONN, when sensitivity was set to 50%, only the 13-analyte ONN with a Δt <1.5 days had a specificity that exceeded 99% (actual value =99.5%), which resulted in a PPV of 17.6%.

The classic delta checks were highly sensitive in identifying MLSPs, but their specificities were lower than all the neural networks at the OOP. When classic delta checks were evaluated on the panel data sets, the highest PPV achieved was 1.7% for the BMP data set with a Δt <1.5 days. The highest PPV achieved using the classic delta checks in the open data sets was 1.9% for the 5–8 analyte data set with a Δt <1.5 days.

Conclusions

Neural networks were created to identify MLS. Using this method, the best AUC achieved was 0.994±0.001 for a CMP PNN with Δt <1.5 days. This study improves upon previous work by increasing the maximum AUC achieved in detecting mislabeled specimen (11). We additionally created neural networks designed to detect MLS when alternative panels were performed, namely BMPs, RFPs, and HFPs. We compared this strategy to an unrestricted approach, where any analyte could be used at either time point. These ONNs were less accurate than the PNNs at detecting MLS, however their flexibility may have some niche applications.

Although the BMP PNN only produced a PPV of 41.7% with a sensitivity of 50%, it is worth highlighting the magnitude of difference in PPV of the PNN when compared to the classic delta checks. The BMP PNN had a 24-fold improvement in PPV when compared to the classic delta checks which had a maximum PPV of 1.7% using the same BMP analytes, though at the sacrifice of sensitivity. The low PPV is in part due to an overly-sensitive classic delta check strategy, which increased both the true-positive rates as well as the false positive rates. A high false positive rate diverts laboratory resources and can become costly to investigate MLS. The analytical tests often need to be repeated, there can be additional blood loss incurred due to the necessity of repeating phlebotomy, and laboratory personnel need to spend time reviewing and analysing the error. The implementation of machine learning-based protocols to detect MLS with fewer false-positive errors may have a dramatic impact on patient care and health care costs, and require little-to-no monetary investment.

One of the strengths and limitations of our study was that pre-existing clinical data obtained from our middleware system was utilized. Using pre-existing data, rather than simulated data, allowed for the direct analysis of realistic scenarios in which the blood-in-tube of the MLS sample could come from any random patient. The limitation of this strategy is that undetected MLS were likely present in the raw data, and these were miscategorized as PLSP in the training and test sets. The effect of undetected MLS pairs in our training and test sets would be expected to have decreased the performance and lowered the AUC of the PNNs and ONNs.

Neural networks and other machine learning strategies have clear advantages over conventional classic delta checks, but these should be implemented with caution due to a number of practical limitations. The algorithms typically generate a “black box” approach to error detection which needs to be evaluated empirically. The strategy relies heavily on the use of contemporary clinical data to train the algorithm. The frequency by which new data must be collected and new neural networks must be trained needs to be established.

Finally, the implementation of machine learning based MLS-detection protocols requires a dedicated understanding of rapidly evolving artificial intelligent technologies. Given the demonstration of improved performance of these protocols over the classic delta checks, laboratory information systems and middleware vendors must be pressed to develop software that can utilize these tools in real-time.

Table S1

| Analyte | Abbreviation | Number of tests | Test pairs | Units | Classic strategy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N pairs with Δt <1.5 days | Absolute change (mean +/− SD) | Relative change (mean +/− SD) | Threshold | Absolute vs. relative | ||||

| Thyroid stimulating hormone | TSH | 97,125 | 128 | 0.23±2.39 | 1.15±0.71 | mcIU/mL | 1 | R |

| Thyroxine | T4 | 4,453 | 12 | −0.30±1.21 | 0.980±0.083 | ng/dL | 1 | R |

| Free thyroxine | FREE T4 | 20,156 | 37 | 0.157±0.494 | 1.09±0.25 | mcg/dL | – | None |

| Triiodothyronine | T3Q | 3,509 | 26 | 24.9±69.3 | 1.24±0.49 | pg/mL | 0.3 | R |

| T-uptake | TUP | 1,131 | 3 | 0.0073±0.0481 | 1.01±0.060 | Ratio | 0.25 | R |

| Estradiol | E2 | 2,705 | 0 | – | – | pg/mL | – | None |

| Testosterone | TSTO | 3,556 | 0 | – | – | ng/mL | – | None |

| Prolactin | PROLAC | 2,571 | 1 | –1.73±0 | 0.858±0 | ng/mL | – | None |

| Progesterone | PROGEST | 638 | 0 | – | – | ng/mL | – | None |

| Total bilirubin | TBILI | 151,747 | 8,982 | −0.04±1.21 | 1.09±0.47 | mg/dL | 0.75 | R |

| Luteinizing hormone | LH | 1,569 | 0 | – | – | mIU/mL | – | None |

| Follicle stimulating hormone | FSH | 2,978 | 0 | – | – | mIU/mL | – | None |

| Cortisol | CORT | 2,802 | 69 | 0.3±10.7 | 1.29±1.40 | mcg/dL | – | None |

| High density lipoprotein cholesterol | HDL | 93,934 | 32 | 0.16±3.15 | 1.01±0.09 | mg/dL | – | None |

| Troponin T | CTNT | 10,182 | 2,339 | −0.24±2.89 | 1.00±0.84 | ng/mL | 0.5 | A |

| L-lactate | LLACT | 12,053 | 6,360 | 0.57±1.90 | 1.46±0.94 | mmol/L | 0.5 | R |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen | CEA | 1,002 | 0 | – | – | ng/mL | – | None |

| Prostate specific antigen | PSA | 16,183 | 5 | −2.32±5.25 | 1.04±0.11 | ng/mL | – | None |

| Creatine phosphokinase | CPK | 31,573 | 6,520 | −30±2180 | 1.19±0.76 | U/L | 0.75 | R |

| Ferritin | FERRI | 14,633 | 9 | −14.1±39.6 | 0.979±0.234 | ng/mL | – | None |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | LDH | 2,335 | 165 | −145±686 | 1.10±0.68 | U/L | 0.9 | R |

| Pro B-type natriuretic peptide | PROBNP | 6,693 | 83 | 460±4740 | 1.07±0.47 | pg/mL | – | None |

| Vitamin B12 | B12 | 14,068 | 6 | −26±187 | 1.00±0.16 | pg/mL | – | None |

| folate, serum | S FOLATE | 5,888 | 4 | 0.815±1.72 | 1.10±0.20 | ng/mL | 1 | R |

| urine protein | U Prot | 3,208 | 1 | 74.0±0 | 3.85±0 | g/24 hrs | – | None |

| human chorionic gonadotropin | HCG | 5,524 | 1 | −61.2±0 | 0.685±0 | mIU/mL | – | None |

| alkaline phosphatase | ALKP | 151,745 | 8,914 | 3.6±46.8 | 1.04±0.22 | U/L | 0.7 | R |

| High sensitivity C-reactive protein | HSCRP | 21,555 | 90 | 27.7±78.0 | 1.67±2.58 | mg/L | – | None |

| Beta-hydroxybutyrate | BOHB | 809 | 513 | 0.97±2.10 | 5.8±17.8 | mmol/L | – | None |

| Albumin | ALB | 155,262 | 9,162 | 0.080±0.379 | 1.03±0.15 | g/dL | 0.3 | R |

| Rheumatoid factor | RF | 4,324 | 0 | – | – | IU/mL | – | None |

| Acetaminophen | ACAM | 138 | 14 | 48.1±75.8 | 9.23±8.66 | mg/L | – | None |

| Blood urea nitrogen | BUN | 285,912 | 113,112 | 0.92±7.41 | 1.09±0.36 | mg/dL | 0.6 | R |

| Urine urea nitrogen | U UREA | 593 | 5 | 19.8±258 | 1.37±0.84 | g/24 hrs | – | None |

| Total cholesterol | CHOL | 94,742 | 38 | 10.2±38.2 | 1.05±0.14 | mg/dL | 0.3 | R |

| Bicarbonate | CO2 | 288,534 | 119,059 | −0.30±2.87 | 0.993±0.140 | mmol/L | 0.5 | R |

| Ammonia | AMON | 1,733 | 78 | 11.1±50.8 | 1.28±0.73 | mcmol/L | 1 | R |

| Gamma glutamyl transferase | GGT | 1,123 | 1 | 1±0 | 1.2±0 | U/L | 0.55 | R |

| Amylase | AMY | 4,531 | 450 | 44±182 | 1.21±0.49 | U/L | 0.75 | R |

| Direct bilirubin | DBILI | 149,189 | 7,807 | −0.011±0.789 | 1.12±0.58 | mg/dL | 0.75 | R |

| Iron | IRON | 11,867 | 22 | 1.43±8.82 | 1.03±0.21 | mcU/dL | – | None |

| Total protein | TP | 152,787 | 8,826 | 0.146±0.626 | 1.03±0.12 | g/dL | 0.3 | R |

| Alanine aminotransferase | ALT | 156,572 | 8,571 | 4±292 | 1.08±0.37 | U/L | 0.8 | R |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | AST | 156,583 | 8,147 | 16±377 | 2.7±99.3 | U/L | 0.8 | R |

| Magnesium | MG | 42,159 | 24,722 | −0.009±0.132 | 0.997±0.174 | mmol/L | 0.5 | R |

| Urine magnesium | U MG | 50 | 1 | 0.88±0 | 1.378±0 | mmol/L | – | None |

| Uric acid | URIC | 6,066 | 334 | 0.18±1.46 | 1.13±0.92 | mg/dL | 0.5 | R |

| Uric acid, urine | U URIC | 80 | 0 | – | – | g/24 hrs | – | None |

| Ethanol | ETOH | 2,403 | 19 | 1530±1270 | 278±909 | mg/L | – | None |

| Calcium | CA | 264,544 | 103,280 | 0.008±0.546 | 1.00±0.07 | mg/dL | 0.1 | R |

| Urine calcium | U CA | 395 | 0 | – | – | mg/24 hrs | – | None |

| Phosphorus | PHOS | 30,784 | 18,717 | 0.04±1.08 | 1.06±0.49 | mg/dL | 0.8 | R |

| Urine phosphorus | U PHOS | 102 | 0 | – | – | mg/dL | – | None |

| Lipase | LIPA | 9,099 | 693 | 86±528 | 1.56±1.87 | U/L | 0.75 | R |

| Glucose | GLUC | 292,116 | 108,102 | 7.2±61.6 | 1.09±0.44 | mg/dL | 1.6 | R |

| Creatinine | CRE | 291,889 | 111,619 | 0.061±0.463 | 1.07±0.46 | mg/dL | 0.8 | A |

| Urine creatinine | UCRE RAN | 19,497 | 9 | 17.4±61.3 | 1.54±1.16 | mg/dL | – | None |

| Salicylate | SALI | 146 | 15 | 114±112 | 50.5±99.5 | mg/L | – | None |

| Triglyceride | TRIG | 90,779 | 76 | 65±267 | 1.14±0.54 | mg/L | 0.75 | R |

| Unsaturated iron binding capacity | UIBC | 11,317 | 19 | 0.2±16.6 | 0.968±0.155 | mcg/dL | 0.4 | R |

| Sodium | NA | 310,234 | 122,406 | −0.19±3.25 | 0.999±0.023 | mmol/L | 8 | A |

| Potassium | K+ | 309,187 | 119,008 | 0.026±0.540 | 1.01±0.14 | mmol/L | 1 | A |

| Chloride | CL | 310,390 | 122,609 | −0.49±4.02 | 0.996±0.038 | mmol/L | 8 | A |

| Haptoglobin | HAPTO | 727 | 22 | −24.4±22.3 | 0.853±0.558 | mg/dL | – | None |

| Immunoglobulin A | IGA | 4,243 | 4 | 26.3±34.5 | 1.05±0.06 | mg/dL | – | None |

| Immunoglobulin M | IGM | 1,944 | 3 | 4.3±10.5 | 1.07±0.12 | mg/dL | – | None |

| Carbamazepine | CARB | 974 | 4 | 0.370±0.940 | 1.03±0.10 | % COHB | – | None |

| Digoxin | DGXN | 849 | 16 | −0.054±0.438 | 1.02±0.33 | mcg/L | – | None |

| Immunoglobulin G | IGG | 2,353 | 3 | 25.0±71 | 1.037±0.078 | mg/dL | – | None |

| Phenobarbital | PHENOB | 415 | 33 | −1.19±4.93 | 0.968±0.174 | mg/L | – | None |

| Phenytoin | DPH | 977 | 58 | −0.50±5.17 | 0.950±0.329 | mg/L | – | None |

| Theophylline | THEO | 61 | 0 | – | – | mg/L | – | None |

| Lithium | LITH | 1,163 | 13 | 0.170±0.388 | 1.49±1.04 | mmol/L | 0.3 | R |

| Valproic acid | VALP | 1,913 | 47 | −3.4±20.3 | 1.04±0.61 | mg/L | – | None |

| C4 complement | C4 | 1,573 | 1 | 1.00±0 | 1.06±0 | mg/dL | – | None |

| Prealbumin | PRE ALB | 4,152 | 41 | 0.71±3.78 | 1.09±0.33 | mg/dL | – | None |

| Direct low density lipoprotein cholesterol | DLDL | 8,400 | 1 | 0.00±0 | 1.00±0 | mg/dL | – | None |

| Urine albumin | UALB | 17,694 | 0 | – | – | mg/24 hrs | 0.9 | R |

| C3 complement | C3 | 1,464 | 1 | 13.0±0 | 1.19±0 | mg/dL | – | None |

| Gentamicin peak | GENT P | 58 | 0 | – | – | mg/L | – | None |

| Gentamicin 6–14 hours post-dose | GENT LVL 6 - 14 POST DOSE | 29 | 0 | – | – | mg/L | – | None |

| Gentamicin trough | GENT T | 90 | 2 | −0.28±1.80 | 1.30±1.15 | mg/L | – | None |

| Tobramycin, peak | TOBRA P | 34 | 0 | – | – | mg/L | – | None |

| Tobramycin | TOBRA | 182 | 3 | −0.570±0.450 | 0.481±0.325 | mg/L | – | None |

| Tobramycin, through | TOBRA T | 83 | 0 | – | – | mg/L | – | None |

| Vancomycin, peak | VANC P | 34 | 0 | – | – | mg/L | – | None |

| Vancomycin, trough | VANC T | 4,587 | 78 | −0.57±8.45 | 1.01±0.44 | mg/L | – | None |

| Urine sodium | U NA | 2,649 | 18 | −23.2±23.3 | 0.530±0.350 | mmol/L | – | None |

| Urine potassium | UK | 2,561 | 17 | −15.9±35.9 | 0.941±0.740 | mmol/L | – | None |

| Urine chloride | U CL | 2,587 | 18 | −32.1± 37.3 | 0.543±0.363 | mmol/L | – | None |

| Kappa free light chains | Kap | 260 | 0 | – | – | – | – | None |

| Lambda free light chains | Lam | 260 | 0 | – | – | – | – | None |

| Alpha fetoprotein | AFP | 876 | 0 | – | – | ng/mL | – | None |

| Cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody | CCP | 246 | 0 | – | – | U/mL | – | None |

| Cancer antigen 125 | CA 125 | 309 | 0 | – | – | U/mL | – | None |

| Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 | CA 19-9 | 125 | 0 | – | – | U/mL | – | None |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate | DHEAS | 145 | 0 | – | – | mcg/dL | – | None |

| Homocysteine | Homocyst T | 198 | 0 | – | – | mcmol/L | – | None |

| Insulin | Insulin | 144 | 0 | – | – | mcU/mL | – | None |

| Hepatitis A total antibody | HepA | 1 | 0 | – | – | – | None | |

| Hepatitis B surface antibody | HepB sAb | 18 | 0 | – | – | IU/L | – | None |

| Parathyroid hormone | PTH | 4,613 | 12 | 12.0±40.9 | 1.18±0.23 | pg/mL | – | None |

| Beta-2-microglobulin | B2MG | 44 | 0 | – | – | mg/L | – | None |

| Alpha 1 antitrypsin | A1AT | 285 | 0 | – | – | mg/dL | – | None |

| Ceruloplasmin | Cerulopl | 353 | 0 | – | – | mg/dL | – | None |

| Free triiodothyronine | Free T3 | 72 | 0 | – | – | pg/mL | – | None |

A, absolute change; N, number; R, relative change; SD, standard deviation.

Table S2

| Neural network type | Δt range (days) | Dataset sizes | Training data | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Validation | Test | Total | % of specimen pairs | Batches/iteration | Iteration drop | Epochs | ||

| PNN-BMP | <1.5 | 148,480 | 18,818 | 18,824 | 186,122 | 19.3 | 300 | 4 | 20 |

| PNN-BMP | 1.5–2.5 | 94,830 | 11,868 | 11,512 | 118,210 | 12.3 | 300 | 4 | 20 |

| PNN-BMP | 2.5–3.5 | 73,594 | 9,210 | 9,202 | 92,006 | 9.5 | 300 | 4 | 20 |

| PNN-BMP | 3.5–5 | 86,744 | 10,900 | 10,932 | 108,576 | 11.3 | 300 | 4 | 20 |

| PNN-BMP | 5–10 | 193,874 | 24,414 | 24,294 | 242,582 | 25.2 | 300 | 4 | 20 |

| PNN-CMP | <1.5 | 8,014 | 1,076 | 1,030 | 10,120 | 1.0 | 40 | 20 | 80 |

| PNN-CMP | 1.5–2.5 | 5,378 | 696 | 618 | 6,692 | 0.7 | 40 | 20 | 80 |

| PNN-CMP | 2.5–3.5 | 4,192 | 530 | 498 | 5,220 | 0.5 | 40 | 20 | 80 |

| PNN-CMP | 3.5–5 | 4,768 | 640 | 622 | 6,030 | 0.6 | 40 | 20 | 80 |

| PNN-CMP | 5–10 | 10,810 | 1,344 | 1,374 | 13,528 | 1.4 | 40 | 20 | 80 |

| PNN-HFP | <1.5 | 10,404 | 1,352 | 1,384 | 13,140 | 1.4 | 40 | 20 | 80 |

| PNN-HFP | 1.5–2.5 | 6,664 | 862 | 808 | 8,334 | 0.9 | 40 | 20 | 80 |

| PNN-HFP | 2.5–3.5 | 5,168 | 662 | 638 | 6,468 | 0.7 | 40 | 20 | 80 |

| PNN-HFP | 3.5–5 | 5,996 | 782 | 816 | 7,594 | 0.8 | 40 | 20 | 80 |

| PNN-HFP | 5–10 | 13,906 | 1,710 | 1,702 | 17,318 | 1.8 | 40 | 20 | 80 |

| PNN-RFP | <1.5 | 2,050 | 274 | 288 | 2,612 | 0.3 | 10 | 20 | 100 |

| PNN-RFP | 1.5–2.5 | 1,460 | 188 | 152 | 1,800 | 0.2 | 10 | 20 | 100 |

| PNN-RFP | 2.5–3.5 | 1,110 | 168 | 148 | 1,426 | 0.1 | 10 | 20 | 100 |

| PNN-RFP | 3.5–5 | 1,302 | 188 | 176 | 1,666 | 0.2 | 10 | 20 | 100 |

| PNN-RFP | 5–10 | 2,478 | 328 | 284 | 3,090 | 0.3 | 10 | 20 | 100 |

| ONN, 5–8 analytes | <1.5 | 110,236 | 13,756 | 13,776 | 137,768 | 14.3 | 100 | 4 | 40 |

| ONN, 5–8 analytes | 1.5–2.5 | 66,002 | 8,226 | 8,152 | 82,380 | 8.5 | 100 | 4 | 40 |

| ONN, 5–8 analytes | 2.5–3.5 | 49,664 | 6,198 | 6,284 | 62,146 | 6.4 | 100 | 4 | 40 |

| ONN, 5–8 analytes | 3.5–5 | 57,074 | 7,094 | 7,174 | 71,342 | 7.4 | 100 | 4 | 40 |

| ONN, 5–8 analytes | 5–10 | 124,404 | 15,522 | 15,448 | 155,374 | 16.1 | 100 | 4 | 40 |

| ONN, 9–12 analytes | <1.5 | 66,962 | 8,344 | 8,622 | 83,928 | 8.7 | 100 | 4 | 40 |

| ONN, 9–12 analytes | 1.5–2.5 | 40,824 | 5,080 | 4,926 | 50,830 | 5.3 | 100 | 4 | 40 |

| ONN, 9–12 analytes | 2.5–3.5 | 32,744 | 3,986 | 3,960 | 40,690 | 4.2 | 100 | 4 | 40 |

| ONN, 9–12 analytes | 3.5–5 | 39,736 | 5,040 | 5,036 | 49,812 | 5.2 | 100 | 4 | 40 |

| ONN, 9–12 analytes | 5–10 | 88,750 | 11,252 | 11,074 | 111,076 | 11.5 | 100 | 4 | 40 |

| ONN, ≥13 analytes | <1.5 | 22,696 | 2,914 | 2,954 | 28,564 | 3.0 | 100 | 4 | 40 |

| ONN, ≥13 analytes | 1.5–2.5 | 13,506 | 1,768 | 1,638 | 16,912 | 1.8 | 100 | 4 | 40 |

| ONN, ≥13 analytes | 2.5–3.5 | 11,296 | 1,416 | 1,384 | 14,096 | 1.5 | 100 | 4 | 40 |

| ONN, ≥13 analytes | 3.5–5 | 13,796 | 1,730 | 1,784 | 17,310 | 1.8 | 100 | 4 | 40 |

| ONN, ≥13 analytes | 5–10 | 33,434 | 4,066 | 4,178 | 41,678 | 4.3 | 100 | 4 | 40 |

BMP, basic metabolic panel; CMP, complete metabolic panel; HFP, hepatic function panel; ONN, open neural network; PNN, panel neural network; RFP, renal function panel.

Table S3

| Δt range (days) | PNN AUC | ONN AUC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP | CMP | HFP | RFP | 5–8 analytes | 9–12 analytes | ≥13 analytes | ||

| <1.5 | 0.966±0.004 | 0.994±0.001 | 0.989±0.001 | 0.943±0.009 | 0.911±0.012 | 0.935±0.004 | 0.964±0.002 | |

| 1.5–2.5 | 0.932±0.011 | 0.980±0.003 | 0.968±0.002 | 0.902±0.007 | 0.870±0.018 | 0.869±0.008 | 0.920±0.010 | |

| 2.5–3.5 | 0.894±0.018 | 0.967±0.004 | 0.950±0.006 | 0.876±0.020 | 0.830±0.014 | 0.833±0.012 | 0.871±0.013 | |

| 3.5–5 | 0.859±0.020 | 0.953±0.007 | 0.930±0.006 | 0.831±0.008 | 0.802±0.011 | 0.795±0.014 | 0.845±0.006 | |

| 5–10 | 0.862±0.007 | 0.954±0.004 | 0.928±0.005 | 0.827±0.011 | 0.805±0.018 | 0.799±0.018 | 0.829±0.005 | |

BMP, basic metabolic panel; CMP, complete metabolic panel; HFP, hepatic function panel; ONN, open neural network; PNN, panel neural network; RFP, renal function panel.

Table S4

| Panel | Δt range (days) | OOP | Sn set to 0.5 | Sn set to 0.8 | Classic | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sn | Sp | PPV | Sn | Sp | PPV | Sn | Sp | PPV | Sn | Sp | PPV | |||||

| BMP | <1.5 | 89.6 | 91.4 | 4.9 | 50.0 | 99.7 | 41.7 | 80.0 | 96.6 | 10.7 | 91.3 | 74.0 | 1.7 | |||

| BMP | 1.5–2.5 | 84.0 | 87.4 | 3.2 | 50.0 | 98.7 | 15.9 | 80.0 | 90.5 | 4.0 | 91.1 | 57.2 | 1.1 | |||

| BMP | 2.5–3.5 | 78.5 | 83.6 | 2.3 | 50.0 | 97.0 | 7.6 | 80.0 | 81.7 | 2.1 | 90.1 | 47.0 | 0.8 | |||

| BMP | 3.5–5 | 75.4 | 79.3 | 1.8 | 50.0 | 94.9 | 4.7 | 80.0 | 73.9 | 1.5 | 91.5 | 39.8 | 0.8 | |||

| BMP | 5–10 | 75.8 | 80.6 | 1.9 | 50.0 | 94.8 | 4.6 | 80.0 | 75.5 | 1.6 | 91.5 | 31.9 | 0.7 | |||

| CMP | <1.5 | 98.4 | 96.4 | 12.1 | 50.0 | 99.9 | 68.1 | 80.0 | 99.4 | 39.2 | 99.6 | 61.4 | 1.3 | |||

| CMP | 1.5–2.5 | 92.3 | 94.3 | 7.5 | 50.0 | 100 | 100 | 80.0 | 99.0 | 28.5 | 99.0 | 37.2 | 0.8 | |||

| CMP | 2.5–3.5 | 90.8 | 92.9 | 6.0 | 50.0 | 99.6 | 36.1 | 80.0 | 97.7 | 14.7 | 100 | 26.5 | 0.7 | |||

| CMP | 3.5–5 | 86.0 | 91.4 | 4.8 | 50.0 | 99.7 | 46.4 | 80.0 | 94.2 | 6.4 | 99.7 | 19.3 | 0.6 | |||

| CMP | 5–10 | 89.3 | 88.5 | 3.7 | 50.0 | 99.4 | 29.0 | 80.0 | 93.8 | 6.1 | 99.4 | 20.1 | 0.6 | |||

| HFP | <1.5 | 96.4 | 95.0 | 8.9 | 50.0 | 99.8 | 61.1 | 80.0 | 99.0 | 28.1 | 99.3 | 61.4 | 1.3 | |||

| HFP | 1.5–2.5 | 89.4 | 92.9 | 6.0 | 50.0 | 99.9 | 66.8 | 80.0 | 97.6 | 14.4 | 99.3 | 37.4 | 0.8 | |||

| HFP | 2.5–3.5 | 88.7 | 89.9 | 4.2 | 50.0 | 99.1 | 21.6 | 80.0 | 94.1 | 6.4 | 99.7 | 26.6 | 0.7 | |||

| HFP | 3.5–5 | 84.5 | 87.1 | 3.2 | 50.0 | 98.8 | 17.2 | 80.0 | 89.5 | 3.7 | 99.5 | 19.1 | 0.6 | |||

| HFP | 5–10 | 85.5 | 84.7 | 2.7 | 50.0 | 98.6 | 15.5 | 80.0 | 88.7 | 3.4 | 98.6 | 21.3 | 0.6 | |||

| RFP | <1.5 | 90.9 | 85.9 | 3.1 | 50.0 | 97.9 | 10.7 | 80.0 | 91.0 | 4.2 | 99.3 | 59.0 | 1.2 | |||

| RFP | 1.5–2.5 | 80.3 | 89.1 | 3.5 | 50.0 | 98.7 | 16.0 | 80.0 | 85.3 | 2.6 | 100 | 42.1 | 0.9 | |||

| RFP | 2.5–3.5 | 84.5 | 82.0 | 2.3 | 50.0 | 93.2 | 3.6 | 80.0 | 82.7 | 2.3 | 100 | 17.6 | 0.6 | |||

| RFP | 3.5–5 | 70.7 | 83.4 | 2.1 | 50.0 | 94.5 | 4.4 | 80.0 | 68.1 | 1.2 | 100 | 14.8 | 0.6 | |||

| RFP | 5–10 | 75.5 | 75.8 | 1.5 | 50.0 | 91.7 | 2.9 | 80.0 | 66.9 | 1.2 | 99.3 | 7.0 | 0.5 | |||

Sensitivity (Sn), specificity (Sp), and positive predictive values (PPV) are reported in percent (%). BMP, basic metabolic panel; CMP, complete metabolic panel; HFP, hepatic function panel; ONN, open neural network; OOP, optimal operating point; PNN, panel neural network; RFP, renal function panel.

Table S5

| N analytes (range) | Δt range (days) | OOP | Sn set to 0.5 | Se set to 0.8 | Classic | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sn | Sp | PPV | Sn | Sp | PPV | Sn | Sp | PPV | Sn | Sp | PPV | |||||

| 5–8 | <1.5 | 80.3 | 84.5 | 2.5 | 50.0 | 97.4 | 8.7 | 80.0 | 84.0 | 2.4 | 82.4 | 78.6 | 1.9 | |||

| 5–8 | 1.5–2.5 | 74.2 | 81.7 | 2.0 | 50.0 | 94.1 | 4.1 | 80.0 | 75.4 | 1.6 | 83.8 | 62.5 | 1.1 | |||

| 5–8 | 2.5–3.5 | 77.0 | 72.4 | 1.4 | 50.0 | 91.9 | 3.0 | 80.0 | 67.8 | 1.2 | 84.4 | 52.2 | 0.9 | |||

| 5–8 | 3.5–5 | 69.1 | 75.5 | 1.4 | 50.0 | 87.9 | 2.0 | 80.0 | 63.7 | 1.1 | 84.4 | 45.9 | 0.8 | |||

| 5–8 | 5–10 | 71.5 | 73.4 | 1.3 | 50.0 | 88.4 | 2.1 | 80.0 | 63.7 | 1.1 | 84.8 | 40.3 | 0.7 | |||

| 9–12 | <1.5 | 86.6 | 84.5 | 2.7 | 50.0 | 99.0 | 19.7 | 80.0 | 90.0 | 3.8 | 89.1 | 68.7 | 1.4 | |||

| 9–12 | 1.5–2.5 | 81.4 | 75.6 | 1.6 | 50.0 | 95.1 | 4.9 | 80.0 | 76.2 | 1.7 | 89.6 | 53.4 | 1.0 | |||

| 9–12 | 2.5–3.5 | 76.5 | 73.8 | 1.4 | 50.0 | 92.3 | 3.1 | 80.0 | 68.9 | 1.3 | 87.5 | 45.6 | 0.8 | |||

| 9–12 | 3.5–5 | 71.7 | 71.1 | 1.2 | 50.0 | 88.5 | 2.1 | 80.0 | 61.2 | 1.0 | 88.6 | 39.7 | 0.7 | |||

| 9–12 | 5–10 | 73.3 | 70.8 | 1.2 | 50.0 | 89.2 | 2.3 | 80.0 | 62.3 | 1.0 | 88.4 | 30.8 | 0.6 | |||

| ≥13 | <1.5 | 90.4 | 88.9 | 3.9 | 50.0 | 99.5 | 35.5 | 80.0 | 95.7 | 8.5 | 93.7 | 64.7 | 1.3 | |||

| ≥13 | 1.5–2.5 | 83.6 | 85.1 | 2.7 | 50.0 | 98.3 | 12.7 | 80.0 | 87.1 | 3.0 | 94.3 | 44.7 | 0.8 | |||

| ≥13 | 2.5–3.5 | 80.3 | 77.2 | 1.7 | 50.0 | 95.5 | 5.2 | 80.0 | 76.3 | 1.7 | 93.9 | 34.5 | 0.7 | |||

| ≥13 | 3.5–5 | 74.5 | 77.5 | 1.6 | 50.0 | 93.3 | 3.6 | 80.0 | 71.0 | 1.4 | 93.6 | 29.1 | 0.7 | |||

| ≥13 | 5–10 | 74.6 | 73.3 | 1.4 | 50.0 | 91.5 | 2.9 | 80.0 | 66.9 | 1.2 | 93.8 | 26.1 | 0.6 | |||

Sensitivity (Sn), specificity (Sp), and positive predictive values (PPV) are reported in percent (%). BMP, basic metabolic panel; CMP, complete metabolic panel; HFP, hepatic function panel; ONN, open neural network; OOP, optimal operating point; PNN, panel neural network; RFP, renal function panel.

Acknowledgments

The research project was possible due to the generous donation of an Nvidia Titan XP graphics processing unit as part of the GPU Research Grant (Nvidia, Santa Clara, California). In addition, this work was supported by the Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Journal of Laboratory and Precision Medicine for the series “Patient Based Quality Control”. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jlpm.2020.02.03). The series “Patient Based Quality Control” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. Mark Cervinski served as an unpaid Guest Editor of the series and serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Journal of Laboratory and Precision Medicine from May 2019 to April 2021. Dr. Jackson reports that the GPU used to perform the research was donated to him by NVIDIA as part of the NVIDIA GPU grant program.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The institutional review board (IRB) at our institution determined that the project is not research involving human subjects as defined by our internal and FDA regulations. IRB review and approval by the organization is not required. The outcomes of the study will not affect the future management of the patients involved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Dzik WH, Murphy MF, Andreu G, et al. An international study of the performance of sample collection from patients. Vox Sang 2003;85:40-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ansari S, Szallasi A. “Wrong blood in tube”: Solutions for a persistent problem. Vox Sang 2011;100:298-302. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wagar EA, Stankovic AK, Raab S, et al. Specimen labeling errors: A Q-probes analysis of 147 clinical laboratories. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2008;132:1617-22. [PubMed]

- Saathoff AM, MacDonald R, Krenzischek E. Effectiveness of Specimen Collection Technology in the Reduction of Collection Turnaround Time and Mislabeled Specimens in Emergency, Medical-Surgical, Critical Care, and Maternal Child Health Departments. Comput Inform Nurs 2018;36:133-9. [PubMed]

- Valenstein PN, Raab SS, Walsh MK. Identification errors involving clinical laboratories: A College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of patient and specimen identification errors at 120 institutions. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2006;130:1106-13. [PubMed]

- Brown JE, Smith N, Sherfy BR. Decreasing Mislabeled Laboratory Specimens Using Barcode Technology and Bedside Printers. J Nurs Care Qual 2011;26:13-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Howanitz PJ, Renner SW, Walsh MK. Continuous wristband monitoring over 2 years decreases identification errors: A College of American Pathologists Q-Tracks study. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002;126:809-15. [PubMed]

- Schifman RB, Talbert M, Souers RJ. Delta check practices and outcomes a q-probes study involving 49 health care facilities and 6541 delta check alerts. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2017;141:813-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balamurugan S, Rohith V. Receiver Operator Characteristics (ROC) Analyses of Complete Blood Count (CBC) Delta. J Clin DIAGNOSTIC Res 2019;13:9-11.

- Yamashita T, Ichihara K, Miyamoto A. A novel weighted cumulative delta-check method for highly sensitive detection of specimen mix-up in the clinical laboratory. Clin Chem Lab Med 2013;51:781-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum MW, Baron JM. Using machine learning-based multianalyte delta checks to detect wrong blood in tube errors. Am J Clin Pathol 2018;150:555-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zweig MH, Campbell G. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) plots: A fundamental evaluation tool in clinical medicine. Clin Chem 1993;39:561-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Jackson CR, Cervinski MA. Development and characterization of neural network-based multianalyte delta checks. J Lab Precis Med 2020;5:10.